Pancreatitis, which is most generally described as any inflammation of the pancreas, is a serious condition that manifests in either acute or chronic forms. Chronic pancreatitis results from irreversible scarring of the pancreas, resulting from prolonged inflammation. Six major etiologies for chronic pancreatitis have been identified: toxic/ metabolic, idiopathic, genetic, autoimmune, recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis, and obstruction. The most common symptom associated with chronic pancreatitis is pain localized to the upper-to-middle abdomen, along with food malabsorption, and eventual development of diabetes.

Treatment strategies for acute pancreatitis include fasting and short-term intravenous feeding, fluid therapy, and pain management with narcotics for severe pain or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories for milder cases. Patients with chronic disease and symptoms require further care to address digestive issues and the possible development of diabetes. Dietary restrictions are recommended, along with enzyme replacement and vitamin supplementation. More definitive outcomes may be achieved with surgical or endoscopic methods, depending on the role of the pancreatic ducts in the manifestation of disease.

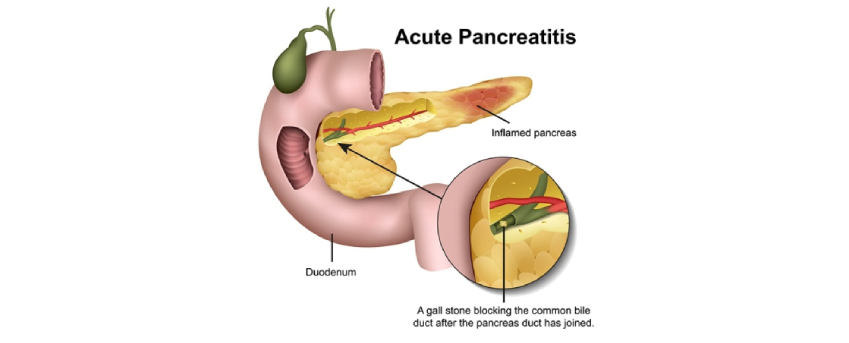

Pancreatitis, which is most generally described as any inflammation of the pancreas, is a serious condition that manifests in either acute or chronic forms. Acute pancreatitis has a sudden onset and short duration, whereas chronic pancreatitis develops gradually and worsens over time, resulting in permanent organ damage.

Epidemiology:

The incidence of acute pancreatitis varies between 5 to 25 cases per 100,000 people. This range may be inaccurate, as many cases may be missed. Death may occur in as many as 10% of patients. The incidence of chronic pancreatitis has not been well studied. One reason for the lack of epidemiological data has been the difficulty in achieving a generalized consensus on the classification and diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, making it difficult to compare between studies.

A more recent study showed a crude incidence rate between 5.8 and 7.7 cases per 100,000 persons, and a prevalence of 26.4 cases per 100,000 persons. Differences are likely due to differences in the amount of alcohol consumed within each region.

Some patients experience recurrent acute pancreatitis, a condition which may be difficult to distinguish from early-stage chronic pancreatitis. The incidence of recurrent acute pancreatitis is not well defined, but has been estimated to be up to 15% among patients who experienced a first acute pancreatitis attack. One study reported an incidence of recurrent acute pancreatitis of 10.9% in patients who experienced a first attack, with 6.4% going on to develop chronic pancreatitis.

The incidence of chronic pancreatitis is highest between 40 and 60 years of age, with a higher rate of occurrence in the male population. Differences in the occurrence of pancreatitis between males and females are likely due to different frequencies of various pancreatitis risk factors associated with each gender. Women have a predilection for the development of gallstones, and therefore, are more likely to develop gallstone-associated pancreatitis. Conversely, men are more likely to have alcohol-induced pancreatitis.

Clinical Presentation:

The most common symptom associated with pancreatitis is pain localized to the upper-to-middle abdomen. Patients often report that their pain radiates to the back. Acute pancreatitis is often associated with nausea or vomiting, and the pain may worsen immediately following a meal. Based on the natural history of chronic pancreatitis, researchers have identified 2 major types of pancreatic pain. Type A pain is defined as having short (<10 day) episodes of acute pain separated by long pain-free periods, whereas type B pain is defined as long (1–2 month) intermittent intervals of severe pain. Type A is experienced more frequently, whereas type B pain is generally more difficult to treat. Although pain is a common symptom of patients with chronic pancreatitis, up to 20% do not experience painful episodes.

Because chronic pancreatitis results in abnormal or diminished pancreatic function, patients may also experience issues related to food malabsorption. Malabsorption is primarily related to a diminished ability to secrete enough pancreatic enzymes to properly digest fats, because pancreatic lipase is the primary pathway of fat digestion. This leads to steatorrhea, bloating, indigestion, dyspepsia, and diarrhoea. Although digestion of carbohydrates and proteins may be diminished, contributions of other body systems (such as salivary amylase for the digestion of carbohydrates and gastric pepsin secretion for the digestion of proteins) limits their malabsorption.

The pancreas is a key component in the regulation of blood sugar levels, and the development of diabetes mellitus is a major complication resulting from chronic pancreatitis or severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Pancreatitis directly causes diabetes as a result of inflammation-induced damage to islet cells, the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas.

Acute pancreatitis inflammation can also lead to pancreatic cell death, or pancreatic necrosis. Often, this necrotized tissue becomes infected, a condition referred to as infected necrosis. Pancreatic necrosis may lead to the development of pancreatic pseudocysts or tissue abscess, common complications associated with pancreatitis. Because pancreatic insults such as alcohol, gallstone disease, and smoking cause repeated pancreatic injury, they must be eliminated in order to reduce the extent of disease and development of permanent glandular damage.

Pathophysiology:

Together, alcohol abuse and gallstones account for over 80% of all cases of acute pancreatitis,however, only a minority of individuals with these risk factors actually develop pancreatitis. One study calculated the estimated annual risk of developing pancreatitis was 0.05–0.2% among patients with gallstones, and further determined that small gallstones were associated with the highest risk. Similarly, 2 studies of patients categorized as heavy drinkers suggested the risk of developing pancreatitis due to alcohol abuse was 2–3%. Other causes of acute pancreatitis have also been identified. Anatomical abnormalities or pancreatic trauma may also contribute to the development of acute pancreatitis. Examples of these structural abnormalities include pancreas divisum (a congenital defect which causes the pancreas ducts to not be properly joined), choledochal cyst (a congenital defect of the bile ducts), and obstructions (such as tumors or strictures). Metabolic disorders such as hypercalcemia and hypertriglyceridemia are also risk factors for acute pancreatitis. Other acute pancreatitis risk factors include exposure to specific medications or toxins and infection.

Chronic pancreatitis can be broadly categorized into 3 etiologies: alcohol abuse, idiopathic, and other. Alcohol abuse is the primary cause of chronic pancreatitis, accounting for approximately 70–80% of all cases.

Chronic pancreatitis causes irreversible scarring of the pancreas, resulting from prolonged inflammation. The most accepted hypothesis regarding the pathogenesis of chronic pancreatitis is the sentinel acute pancreatitis event (SAPE) hypothesis, in which an initial insult or injury to the pancreas results in acute pancreatitis. A migration of stellate cells and inflammatory reactions subsequently occurs. Repeated and prolonged pancreatic inflammation leads to the accumulation of collagen and matrix proteins. Cytokines such as tumor growth factor beta (TGFb) cause fibrosis and scarring of the pancreatic tissue, which can result in decreased pancreatic function.